Sign up for:

- Information on TM research and webinars

A Scientist Reviews Three Types of Meditation An Interview with David Orme-Johnson, Ph.D.

Are there real differences between different meditation practices—or are all meditation techniques essentially the same? After more than 40 years of scientific research, scientists have concluded that there are distinct differences in the way different meditation techniques are practiced, in the effects they have on the brain and body, and their outcomes.

Research psychologist David Orme-Johnson, Ph.D., has published over 100 studies and served as principal investigator in research sponsored by the NIH. Here he explains the distinct differences between three categories of meditation techniques.

Q: What are the three types of meditation and where did these categories originate?

Dr. Orme-Johnson: Different meditation techniques follow different procedures and have different outcomes, and these effects can be measured. Published research by Lutz, et al, had organized meditation practices according to their different procedures. In a paper published in

Consciousness and Cognition in 2010, Dr. Fred Travis and Dr. Jonathan Shear reviewed the research and organized meditation techniques

into three categories: Focused Attention, Open Monitoring, and Automatic Self-Transcending. These categories are a good place to start the discussion.

into three categories: Focused Attention, Open Monitoring, and Automatic Self-Transcending. These categories are a good place to start the discussion.

Q: Which category does TM fall under?

Dr. Orme-Johnson: TM is the primary example of Automatic Self-Transcending. The TM technique allows the mind to easily and effortlessly settle inward, through quieter levels of thought, until you automatically experience the most silent and peaceful level of your own awareness—pure consciousness.

The purpose of Automatic Self-Transcending is to enliven a state of consciousness that has global benefits for the mind and body. Research shows that when one transcends, the level of biochemical and physiological stress decreases. Essentially, TM creates the opposite effect of the classic stress/fight-or-flight response. Research shows that during TM, heart rate decreases, respiratory rate decreases, levels of cortisol decrease, and so forth.

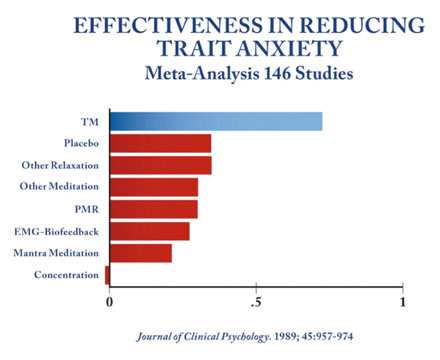

The positive effects continue outside of meditation and are long-term. Hundreds of peer-reviewed research studies have reported increased focus and mental clarity and reduced anxiety and depression. TM practice has also been found to strengthen the immune system and reduce medical care utilization and costs in all categories of disease by an average of 50 percent. Well-controlled, NIH -sponsored studies have shown that TM reduces blood pressure and improves metabolic syndrome. A 2013 scientific statement from the American Heart Association reported that the Transcendental Meditation technique is the only meditation practice that has been shown to lower blood pressure.

Q: What about Focused Attention meditation?

Dr. Orme-Johnson: Focused Attention typically involves concentrating to prevent the mind from wandering. The focus could be a candle flame or the breath or another object. The idea is to train your mind to hold its focus on one thing, even though it may want to jump around like a monkey. Studies cited in the November 2014 issue of Scientific American suggest that practicing Focused Attention has some effect in improving the ability to focus.

Q: And Open Monitoring?

Dr. Orme-Johnson: The purpose of Open Monitoring is to develop an emotionally non-reactive, non-judgmental response to thoughts and sensations that stream through the mind. The goal is that even outside of meditation you will be able to catch yourself, to control your spontaneous emotional reaction. Mindfulness meditation frequently is associated with Open Monitoring, although it sometimes involves Focused Attention practices.

Scientific American described how open monitoring/mindfulness is used to treat depression. “By deliberately monitoring and observing their thoughts and emotions when they feel sad or worried, depressed patients can use [open monitoring] meditation to manage negative thoughts and feelings as they arise spontaneously and so lessen rumination,” authors Lutz and Davidson said.

However, in a recent NY Times Op Ed, prominent mindfulness researchers, neuroscientist Richard Davidson and psychologist Alfred Kaszniak, are quoted as saying, “There are still very few methodologically rigorous studies that demonstrate the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in either the treatment of specific diseases or in the promotion of well-being.”

Q: What about brainwave activity in these three categories of techniques?

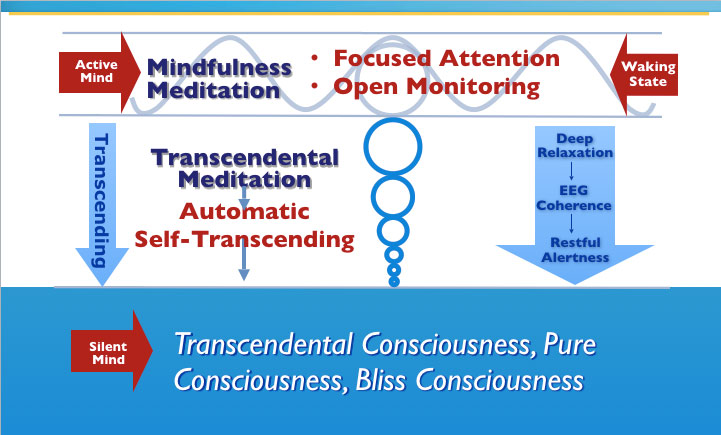

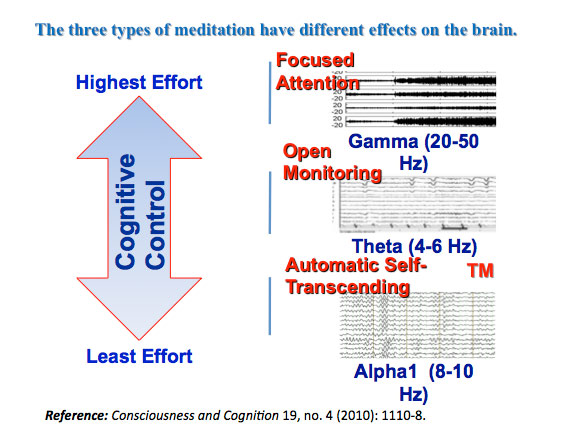

Dr. Orme-Johnson: Travis and Shear’s research review showed that the three categories of meditation produced three distinctly different EEG frequencies.

Focused Attention produces high frequency beta/gamma (13 - 50 Hz) EEG, which is associated with mental effort. High frequency (think of a high pitched tone) is not a restful, calm, transcendental state, but an active state observed when someone is concentrating in a highly focused manner.

Open Monitoring is characterized by a slower EEG called theta (4-6 Hz), which occurs when someone is inwardly preoccupied, unaware of the noises or people around them. Theta is associated with the thalamus, the central sensory switchboard that reduces awareness of incoming information.

Q: And Automatic Self-Transcending?

Dr. Orme-Johnson: During the Transcendental Meditation technique, you see a middle-frequency EEG, called alpha1 (8-10 Hz). Alpha1 is characteristic of reduced mental activity and relaxation.

Alpha1 is also associated with orderly brain-wave activity. For instance, a meta-analysis published in the American Psychological Association’s Psychological Bulletin in 2006 cited seven studies on TM practice showing that alpha1 coherence first occurs between the left and right frontal lobes of the brain. It continues spreading until the whole brain becomes synchronized and coherent.

This is significant because alpha1 coherence (orderliness) organizes the functioning of different brain areas to work together for better memory, creativity, perception, and motor behavior. Similar to when a conductor waves his baton to synchronize a symphony, the coherent frontal alpha waves create harmonious brain functioning that effortlessly transforms the way we function even after meditation.

Q: It seems the TM technique is unique because it does not involve concentration or control, either during the practice or in activity.

Dr. Orme-Johnson: Yes, in many ways, the TM technique is the opposite of other practices. For one thing, TM does not involve concentration, which limits the brain’s functioning to one area of focus. Rather, TM is completely effortless, creating a state of restful alertness that is correlated with global coherence of the entire brain.

Secondly, the Transcendental Meditation technique doesn’t teach us how to cope with stress through cognitive manipulation. Rather, when the body is given the opportunity to experience deep rest, it spontaneously dissolves deep-rooted stress at its basis and heals itself.

This combination of deep rest and increased orderly brain functioning results in the long-term mental and physical health benefits that have been substantiated by over 350 published peer-reviewed research studies.

References

Brook, R. et al. (2013). Beyond medications and diet: alternative approaches to lowering blood pressure. Hypertension: Journal of the American Heart Association, 61 (6).

Cahn, B. R., Delorme, A., & Polich, J. (2010). Occipital gamma activation during Vipassana meditation. Cognitive Processes, 11(1), 39-56.

Orme-Johnson, D. W., & Walton, K. G. (1998). All approaches of preventing or reversing effects of stress are not the same. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(5), 297-299.

Ricard, M., A. Lutz, and J.R.T. Davidson, (November 2014). Mind of the meditator. Scientific American, (Vol 311 (5) p.39-45.

Lutz, A., et al., Mental Training Enhances Attentional Stability: Neural and Behavioral Evidence. Journal of Neuroscience, 2009. 29(42): p. 13418-13427.

Travis, F., & Shear, J. (2010). Focused attention, open monitoring, and automatic self-transcending: Categories to organize meditations from Vedic, Buddhist, and Chinese traditions. Consciousness and Cognition, 19 (4): 1110-8.

Travis, F.T., et al., Effects of Transcendental Meditation practice on brain functioning and stress reactivity in college students. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 2009. 71(2): p. 170-176.

Orme-Johnson, D.W., Autonomic stability and Transcendental Meditation. Psychosom Med, 1973. 35(4): p. 341-9.

Alexander, C.N., et al., Effects of Transcendental Meditation compared to other methods of relaxation and meditation in reducing risk factors, morbidity and mortality. Homeostasis, 1994. 35(3-4): p. 243-264.

Barnes, V.A. and D.W. Orme-Johnson, Prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease in adolescents and adults through the Transcendental Meditation program®: A research review update. Current Hypertension Reviews, 2012. 8(3): p. 227-242.

Orme-Johnson, D.W., V.A. Barnes, and R.H. Schneider, Transcendental Meditation for the Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease in Heart & Mind: the Practice of Cardiac Psychology (2nd edition), R. Allan and J. Fisher, Editors. 2011, American Psychological Association: Washington, DC.

Alexander, C.N., P. Robinson, and M.V. Rainforth, Treating alcohol, nicotine and drug abuse through Transcendental Meditation: A review and statistical meta-analysis. Alcohol Treatment Quarterly, 1994. 11: p. 13-87.

Eppley, K., A.I. Abrams, and J. Shear, Differential effects of relaxation techniques on trait anxiety: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1989. 45(6): p. 957–974.

Orme-Johnson, D.W., Transcendental Meditation: Clinical roundup on anxiety. Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 2013. 19(6): p. 341.

Orme-Johnson, D.W. and V.A. Barnes, Effects of the Transcendental Meditation technique on Trait Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 2013. 20(5): p. 330-341.

Sedlmeier, P., et al., The psychological effects of meditation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 2012. 138(6): p.1139-71.

Elder, C., et al., Effect of Transcendental Meditation on employee stress, depression, and burnout: A randomized controlled study. The Permanente Journal, 2014. 18(1): p. 19-23.

Infante, J.R., et al., Levels of immune cells in transcendental meditation practitioners. International Journal of Yoga, 2014. 7(2): p. 147-151

Orme-Johnson, D.W., Medical care utilization and the Transcendental Meditation program. Psychosomatic Medicine, 1987. 49: p. 493-507.

Herron, R. and K. Cavanaugh, Can the Transcendental Meditation program reduce the medical expenditures of older people? A longitudinal cost reduction study in Canada. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 2005. 17: p. 415-442.

Schneider, R.H., et al., A randomized controlled trial of stress reduction in the treatment of hypertension in African Americans during one year. American Journal of Hypertension, 2005. 18(1): p. 88-98.