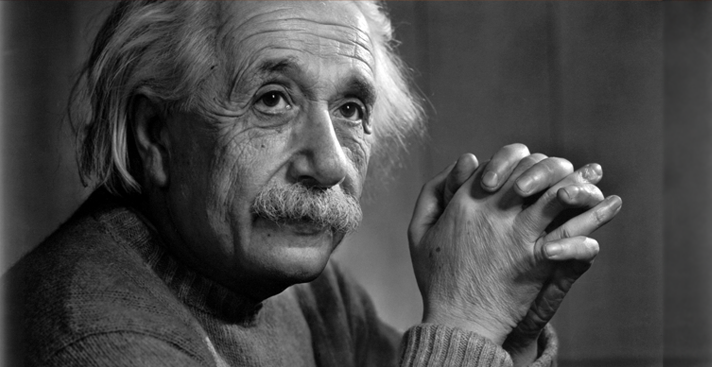

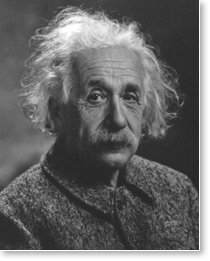

Albert Einstein is widely regarded as one of the greatest scientists who ever lived. The totality of his work converges into one supreme goal: to understand the unity underlying nature’s diversity.

His theory of special relativity (1905) showed the underlying unity of matter and energy and of light and time. His theory of general relativity (1916) showed the unity of gravity and acceleration, of space and time, and of matter and space.

Einstein profoundly altered the way we think of ourselves and the universe. He spent the last half of his life trying to develop a unified field theory, a description of the one field which, he felt certain, underlies and gives rise to all the forces in nature. He persisted despite criticism from fellow physicists.

As it turned out, two of the four fundamental forces of nature (the strong and weak nuclear forces) were not well understood until several decades after Einstein’s death, nor had the mathematical tools become available to accomplish the unity he sought.

As it turned out, two of the four fundamental forces of nature (the strong and weak nuclear forces) were not well understood until several decades after Einstein’s death, nor had the mathematical tools become available to accomplish the unity he sought.

Yet though Einstein himself did not complete his quest, the theory of unity he intuitively felt and assiduously sought inspires the modern quest for a “theory of everything.” This quest is nearing completion today, in the form of the so-called superstring or unified field theories.

Where did Einstein’s conviction of nature’s underlying unity come from? What impelled his life’s work, despite the criticism and lack of success in the latter decades?

Einstein himself gives us a clue in a letter he wrote to Queen Elizabeth of Belgium (1876-1965) that contains the following passage:

Still there are moments when one feels free from one’s own identification with human limitations and inadequacies. At such moments, one imagines that one stands on some spot of a small planet, gazing in amazement at the cold yet profoundly moving beauty of the eternal, the unfathomable: life and death flow into one, and there is neither evolution nor destiny; only being. [1]

Here Einstein describes experiences he apparently had of an underlying reality of life — not only beyond space and time but beyond life and death, beyond evolution and destiny. And what does he experience at this level? “Only being,” he tells us.

Einstein’s words call to mind Maharishi’s teaching that at the basis of all of life, inner and outer, is a field of pure existence, “pure Being,” as he called it early on — an unmanifest field of pure consciousness, of limitless intelligence and creativity. This field, Maharishi explained, forms the source of everything in the universe; all the forms and phenomena of creation are but waves on the ocean of Being.

Maharishi, moreover, put forward a technique for experiencing this inner field of life. This is the Transcendental Meditation technique — simple, natural, and effortless. When we practice this technique, mental activity settles effortlessly inward; the mind moves beyond (transcends) the thinking process and expands into the ocean of pure consciousness within — the Self. Simultaneously the body settles down to a uniquely deep state of rest, dissolving stress and restoring physiological balance.

This state proved to be a fourth major state of consciousness, distinct from waking, dreaming, and deep sleep. Maharishi called it Transcendental Consciousness and explained that regular practice of the Transcendental Meditation technique — that is, regular experience of this fourth state — is the key to developing our latent inner potentials and higher states of consciousness. Over the past 40 years, hundreds of scientific research studies have born this out — documenting increased intelligence and creativity, balanced personality growth, improved health, enhanced relationships, even greater harmony and peace in the surrounding environment.

This state proved to be a fourth major state of consciousness, distinct from waking, dreaming, and deep sleep. Maharishi called it Transcendental Consciousness and explained that regular practice of the Transcendental Meditation technique — that is, regular experience of this fourth state — is the key to developing our latent inner potentials and higher states of consciousness. Over the past 40 years, hundreds of scientific research studies have born this out — documenting increased intelligence and creativity, balanced personality growth, improved health, enhanced relationships, even greater harmony and peace in the surrounding environment.

Maharishi emphasized that when we transcend, we experience not merely the source of thought but the ocean of intelligence from which the whole universe is born and sustained. We gain what he called the support of nature to fulfill our desires with increasing ease. As higher states of consciousness develop, we come to recognize, as a direct experience, the ultimate unity of life, the reality that everything in the universe is nothing other than an experience of our own Self, infinite and eternal.

Einstein alluded to this in a letter he wrote in 1950:

A human being is a part of the whole, called by us “Universe,” a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separate from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty. [2]

Einstein’s quest for unity, it appears, was no mere intellectual exercise. He sought to understand, through the methodology of modern science, what he experienced deep within. This experience, for Einstein, was all important.

Einstein’s quest for unity, it appears, was no mere intellectual exercise. He sought to understand, through the methodology of modern science, what he experienced deep within. This experience, for Einstein, was all important.

The finest emotion of which we are capable is the mystic emotion. Herein lies the germ of all art and all true science. Anyone to whom this feeling is alien, who is no longer capable of wonderment and lives in a state of fear is a dead man. To know that what is impenetrable for us really exists and manifests itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty, whose gross forms alone are intelligible to our poor faculties — this knowledge, this feeling . . . that is the core of the true religious sentiment. In this sense, and in this sense alone, I rank myself among profoundly religious men. [3]

The “mystic emotion” Einstein refers to does not imply “mysterious” or “incomprehensible.” The word mystic stems from Greek word meaning, simply, to close, i.e., the eyes. In the Transcendental Meditation technique we have a simple procedure for closing the eyes, diving within, and experiencing the field of pure consciousness, “the germ of all art and all true science,” as Einstein worded it — indeed, the germ of all creation.

This, for Einstein, was the goal of human life:

The true value of a human being is determined primarily by the measure and the sense in which he has attained to liberation from the self. [4]

“Liberation from the self,” in Maharishi’s understanding, means transcending the individual self — the self related to our mind and our ego — and experiencing the universal Self, the field of unbounded pure consciousness. Glimpses of this magnificent, sublime experience propelled Einstein’s quest to understand the ultimate unity of life. And this experience, thanks to Maharishi, is now easily available to everyone.

“Liberation from the self,” in Maharishi’s understanding, means transcending the individual self — the self related to our mind and our ego — and experiencing the universal Self, the field of unbounded pure consciousness. Glimpses of this magnificent, sublime experience propelled Einstein’s quest to understand the ultimate unity of life. And this experience, thanks to Maharishi, is now easily available to everyone.

REFERENCES

[1] Jeremy Bernstein, Einstein (New York: Viking Press, 1973), 11.

[2] From a 1950 letter, quoted in Walter Sullivan, “The Einstein Papers: A Man of Many Parts,” New York Times, March 29, 1972, 22M.

[3] Quoted in Peter Barker and Cecil G. Shugart, eds., After Einstein: Proceedings of the Einstein Centennial Celebration at Memphis State University (Memphis State University Press, 1981), 179.

[4] Albert Einstein, The World As I See It I (New York: Open Road / Philosophical Library, 2011), 10.