The more scientists explore the effects of the daily practice of the Transcendental Meditation technique on mind, body and behavior, the more amazing the range of TM’s practical benefits becomes. However, in addition to these individual benefits, there is a holistic result of the daily TM practice that has a profound impact on the development of enlightenment.

The more scientists explore the effects of the daily practice of the Transcendental Meditation technique on mind, body and behavior, the more amazing the range of TM’s practical benefits becomes. However, in addition to these individual benefits, there is a holistic result of the daily TM practice that has a profound impact on the development of enlightenment.

The excerpt below from the book, Transcendental Meditation: The Essential Teachings of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, writer Jack Forem provides some insight into one of the dimensions of this holistic inner development.

INNER AND OUTER FREEDOM

Freedom is one of the more frequently used words in our age. Politicians use it incessantly, and the media is not far behind. But what does it really mean? What is a free man or woman, a free action, a free society?

First of all, we ought to distinguish between two kinds of freedom. These correspond to the two aspects of life we have been discussing: inner and outer.

Outer freedom is freedom of action. Defined in its simplest terms, it means that people can do what they please, that no individual or institution will stand between their desire and its fulfillment. It means the ability to openly express any opinion, to move from one place to another unhindered, and so on. We might call these aspects political or social freedom. They are governed by the laws of society. But even more, they are governed by the level of consciousness of that society.

The more enlightened a community or society is—the more its citizens are broad-minded, concerned about the welfare of their fellow residents on the planet, and living at a high level of individual fulfillment and happiness—the more there will be freedom in that society. The more narrow a society is, the more its population is driven by suspicion, fear, anger, hatred, violence, and intolerance, the less freedom exists and can exist. It’s an old truth: as a person is within, so will his or her outward actions be; as individuals are, so will society be. “By their fruits ye shall know them.”1

Knowing this, Maharishi did not concern himself with the external aspects of freedom. His energies were directed toward bringing each person to a state of inner freedom or liberation from the bondage of ignorance—ignorance of one’s own nature and its immense potentialities. For as long as individuals are bound by limited vision and negative emotions, it matters little whether they go north or south, wear red or blue, eat rice or potatoes—they are not free, for they carry with them the prison of their own shortcomings, which restrict their understanding, their feelings, and their actions.

FREEDOM AND SELF-REALIZATION

In Escape from Freedom, psychologist and social philosopher Erich Fromm suggested that the key to freedom is self-realization. “The realization of the self,” he wrote, “is accomplished . . . by the realization of man’s total personality, by the active expression of his emotional and intellectual potentialities. . . . In other words, positive freedom consists in the spontaneous activity of the total, integrated personality.”2

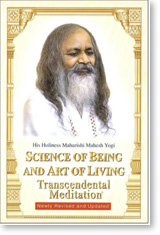

Fromm’s view is entirely consistent with what Maharishi wrote in Science of Being and Art of Living

“As long as the mind does not function with its full potential and is not in a position to use all the faculties it has, its freedom is restricted. Therefore the first important step in making the mind really free is the full unfoldment of its potentialities.”3

I think most of us accept the truth of this principle… and acknowledge and embrace the importance of self-realization, but how do we do that?

WHAT IS THE SELF?

What exactly is the self that we are asked to realize or know? Is it the body, with all its limbs and organs? This is certainly part of what we are, but there must be something deeper, for the body changes, grows, and is completely renewed every seven years, yet some continuity remains to retain our identity.

Is the self our thoughts, our feelings, our memories, our desires, our likes and dislikes? Yes, surely. But these things change, too. What we care about or value today, tomorrow may seem foolish or unimportant. Our moods and values change; our perceptions change. Is the self no more than this ever-changing, unstable, limited mind and body, full of undeveloped capabilities and unresolved longings, this storehouse of memories and desires? If this were so, where would be the freedom in knowing such a self? Where would be the freedom in actualizing a restricted, ever-changing self, bound by time, space, and causation, by the ephemeral nature of life with its constant vicissitudes? It would certainly be a tenuous and limited type of freedom.

But what if the true nature of the Self, in its deepest aspect, were eternal and unchanging, infinite in intelligence, energy, and happiness? “He is never born, nor does he ever die,” says the Bhagavad Gita of the true, essential Self of everyone:

Unborn, eternal, everlasting, ancient, he is not slain when the body is slain. . . . These bodies are known to have an end; the dweller in the body is eternal, imperishable, infinite. . . . He is eternal, all-pervading, stable, immovable, ever the same. He is declared to be unmanifest, unthinkable, unchangeable.4

If this were the essential nature of our Self, more deeply and truly who we are than the whole relative bundle of constantly shifting thoughts, feelings, desires, and memories—which will always be part of who we are—then self-realization and “know thyself” would have an entirely fresh and different meaning. If you knew yourself to be eternal and unbounded, if you felt grounded in a field of stability and peace, unshakable and strong no matter what experiences came along in the ever-changing sphere of life, you would be free. That is, if this were your experience—knowledge in the most profound sense, beyond mere intellectual understanding. If this were your direct perception and an awareness you had at all times, then nothing could overthrow your freedom. In all circumstances, you would know yourself to be free. Maharishi calls this state of liberation Cosmic Consciousness, and facilitating every individual’s journey to this state is one of the principal goals of the Transcendental Meditation program.

“The bliss of this state eliminates the possibility of any sorrow, great or small. Into the bright light of the sun no darkness can penetrate. No sorrow can enter bliss-consciousness, nor can bliss-consciousness know any gain greater than itself. This state of self-sufficiency leaves one steadfast in oneself, fulfilled in lasting contentment.”5 —Maharishi

FREEDOM FROM FEAR

Many of the people I interviewed reported that anxiety and fears diminished or seemed to vanish after beginning TM, a personal experience supported by substantial research. “Even a slight practice of Transcendental Meditation relieves great fears,” Maharishi said. Freedom and fear cannot easily coexist.

Fear eliminates choice, and prevents realistic evaluation and spontaneous response. The physiological alarm bells of fear reverberate through the body and disrupt the biochemical balance. The well-known “fight or flight” response is a perfect example: our choices are instantly narrowed to two, and we become a prisoner of the body’s chemistry.

When fear diminishes, openness to the possibilities of the moment increases, and freedom grows. “Many of my fears have left me,” said a young woman, “and it’s easier for me in my associations with others. The area of social contacts has always been hard for me because I’m very shy by nature, but through meditation, I find this situation getting better each day.”

As consciousness evolves, the Self becomes gradually more present in one’s awareness, until we know it in its true status as greater than the personal ego with its endless concerns. If I know myself to be eternal, immortal, and unbounded—not my body, of course, which remains subject to the limitations of time and space, but my consciousness, who I feel I am—then what is there to worry about or fear? Again, we’re talking about a knowing that is experienced, not just an idea or even a strong conviction.

Maharishi explained this at length in his Translation and Commentary on the Bhagavad Gita. Here is a representative passage:

“The mind, which has gained the state of bliss-consciousness through Transcendental Meditation, remains naturally contented on coming out from the transcendental state to the field of activity. This contentment, being grounded in the very nature of the mind, does not allow the mind to waver and be affected in pleasure or pain, nor allow it to become affected by attachment or fear in the world.”5

FREEDOM FROM MISTAKES

….Many people are unaware of the constant stream of thoughts flowing in their minds day and night, and they may be particularly unaware of how much of this thought content is tinged with negativity. “I hate my job . . . my boss . . . the commute to work . . .” and so on, or, “Why can’t I make my relationships work?” “Why do I always say things like that?”

As long as we don’t realize we are having these thoughts, there’s nothing we can do about it. Meditation begins to open an interior space in which we become conscious of the flow of thoughts. We start to see that we are not the thoughts, but rather, a witness to them: they come and go and we remain, able to observe them, still here after they are gone. That awareness provides a place to stand, a point of leverage from which we have the power to reject some thoughts (No point complaining about the traffic, there’s nothing I can do about it) and choose others (While I’m stuck here, I might as well plan the report I need to write). In other words, instead of just sitting still in the dark, we can begin to take a director’s role in the ongoing movie in our minds.

This is a good development, and begins to confer real freedom. Instead of being a helpless victim to the onrushing thoughts, which may poison our minds and lead to actions whose consequences we regret, we can select from the infinite pool of possible thoughts something more positive, uplifting, or useful. We become able to respond beneficially, rather than merely react.

The ultimate freedom comes to those who persevere with meditation, clear their minds and bodies of the accumulated stresses that are the breeding ground for negative thoughts and behaviors, and steadily awaken to the enlightened state of life in which positive (life-supporting, evolutionary) thinking and acting are natural, spontaneous, and unforced. As we move toward that state, the inner “space” of freedom—the gap between thoughts when we are aware of them—becomes wider, and our freedom of choice more tangible and profound.

The key that most effectively opens the door to this growth of freedom is transcendence.

References:

1. Matthew 7:20

2. Escape from Freedom (New York: Rinehart, 1941), page 258

3. Science of Being and Art of Living, pages 234-235.

4. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi On the Bhagavad Gita, II, 18-25

5. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi On the Bhagavad Gita, II, 56

Jack Forem met Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and learned the Transcendental Meditation technique in 1966. After studying with Maharishi in India in 1970, Forem served as head of the TM Center in New York City and on Maharishi’s international staff. His bestselling book, “Transcendental Meditation: The Essential Teachings of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi” was originally published in 1973. An updated edition was published in 2012.