1885–1930 • ENGLAND

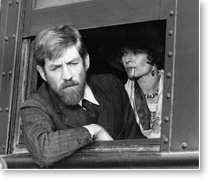

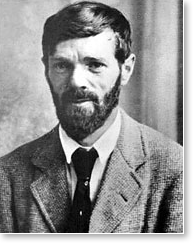

The English novelist E.M. Forster called him “the greatest imaginative novelist of our generation.”1 D.H. Lawrence began his working life as a teacher while also writing poems, short stories, and a novel. Publishing his work early, he was able to devote himself full-time to writing.

He spent much of his life traveling — to Italy and Sicily, Australia, Sri Lanka, the United States, Mexico, France — writing novels while gaining fame as a travel writer. He wrote 13 novels, over 400 poems, four travel books, an acclaimed study of American literature, other literary criticism, and translations of Russian and Italian authors. His letters are published in eight volumes. He was also an avid oil painter. Through all of his work, he was concerned with the dehumanizing influence of modern industrialized society.

The following passage comes from Lawrence’s novel The Rainbow. The main character is caring for a small child and is seeking shelter from a storm.

He opened the doors, upper and lower, and they entered into the high, dry barn, that smelled warm even if it were not warm. He hung the lantern on the nail and shut the door. They were in another world now. The light shed softly on the timbered barn, on the white-washed walls, and the great heap of hay; instruments cast their shadows largely, a ladder rose to the dark arch of a loft. Outside there was the driving rain, inside, the softly illuminated stillness and calmness of the barn.

Holding the child on one arm, he set about preparing the food for the cows, filling a pan with chopped hay and brewer’s grains and a little meal. The child, all wonder, watched what he did. . . . She was silent, quite still.

In a sort of dream, his heart sunk to the bottom, leaving the surface of him still, quite still. . . .

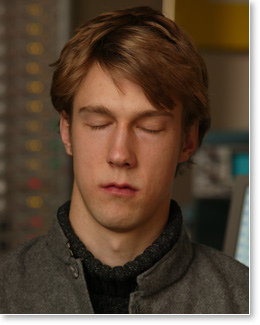

The two sat very quiet. His mind, in a sort of trance, seemed to become more and more vague. He held the child close to him. . . . Gradually she relaxed, the eyelids began to sink over her dark, watchful eyes. As she sank to sleep, his mind became blank.

When he came to, as if from sleep, he seemed to be sitting in a timeless stillness.2

Lawrence describes the experience of the mind becoming still while remaining awake. After the man enters the barn, his mind moves inward (“his heart sunk to the bottom”) and becomes increasingly settled until, finally, “his mind became blank.” Yet he is not asleep — in some way he remains awake.

If you practice the Transcendental Meditation technique, you’ll recognize the process of transcending in this description. When we transcend, the mind settles inward, moving through subtler levels of awareness. Then the mind transcends thought altogether, leaving consciousness alone and awake within itself. We experience consciousness in its pure state — silent, serene, unbounded, like an ocean having become calm.

Even the setting acts as a metaphor for transcendence. Lawrence describes the barn as “another world.” Outside is the driving rain, inside “the softly illuminated stillness and calmness of the barn.”

When the man’s mind becomes active again, he feels he remains in a “timeless stillness.” Each time we transcend during Transcendental Meditation practice, the mind retains something of the experience of pure consciousness, indicating that our mental potential is growing.

It’s not surprising that someone like D.H. Lawrence, with his profuse creativity, would have this inner experience. The field of pure consciousness is an infinite reservoir of creativity and intelligence. It is the source of thought, the source of every form of creative expression, the wellspring of genius. Highly creative people are highly creative because, by some good luck, they have greater access to this inner ocean of creativity.

“My life draws strength from the depth of the universe”

Toward the end of his life Lawrence wrote an essay entitled “The Real Thing.” If you didn’t know it was written in the 1920s, you could easily believe it had been written today. He writes about how so many young people have “gone through everything and reached a stage of emptiness and disillusion,” a phenomenon he says is unparalleled in the last 1,500 years. “They begin to realize that, if they are not careful, they will have missed life altogether,” he writes.

They, the smart young who are so swift at hopping to a thing, to have missed life itself, not to have hopped onto it! . . . Let the chance slip by, while they were fooling around! The young are just beginning uneasily to realize that this may be the case. They are just beginning to realize that all that “life” which they lead, rushing around and being so smart, perhaps isn’t life after all, and they are missing the real thing.

What then? What is the real thing? Ah, there’s the rub. There are millions of ways of living, and it’s all life. But what is the real thing in life. What is it that makes you feel right, makes life really feel good?

Lawrence continues, offering an answer based on his own experience:

It is the great question. And the answers are the old answers. But every generation must frame the answer in its own way. What makes life good to me is the sense that, even if I am sick and ill, I am alive, alive to the depths of my soul, and in touch, somewhere in touch with the vivid life of the cosmos. Somehow my life draws strength from the depth of the universe, from the depth among the stars, from the great “World.” Out of the great World comes my strength, and my reassurance. One could say “God,” but the word “God” is somehow tainted. But there is a flame or a Life Everlasting wreathing through the cosmos forever and giving us our renewal, once we can get in touch with it.

What makes life good to Lawrence, in other words, is feeling connected to something deep, transcendental — to the source of everlasting life throughout the cosmos. One only need connect with it, he says.

When people “lose their contact with this eternal life-flame,” he goes on, that’s when things go wrong.

And then there is nothing for men to do but to turn back to life itself. Turn back to the life that flows invisibly in the cosmos, and will flow for ever, sustaining and renewing all living things. It is not a question of sins or morality, of being good or being bad. It is a question of renewal, of being renewed, vivified, made new and vividly alive and aware, instead of being exhausted and stale, as men are today. How to be renewed, reborn, revivified? That is the question men must ask themselves, and women too.

And the answer will be difficult. Some trick with glands or secretions, or raw food, or drugs won’t do it.

Neither will some wonderful revelation or message. It is not a question of knowing something, but of doing something. It is a question of getting into contact again with the living center of the cosmos. And how are we to do it?3

He ends his essay with this question — how are we to do it?

Pure consciousness and the unified field

The field of pure consciousness, the inner ocean of unbounded creativity and intelligence, is not just the source of thought, the source of human creativity — it is the source of nature’s infinite creativity, the field of pure intelligence that maintains orderliness throughout the universe. Pure consciousness is identical with the unified field of natural law, as described mathematically by modern theoretical physics. The depth of the soul is identical with the “depth of the universe,” to quote Lawrence. The “Life Everlasting wreathing through the cosmos forever” lies within us.

We find this principle expressed in the world’s major religious. The terminology varies, but the idea is the same: There is a field of unity underlying nature’s phenomenal diversity, and we all have access to it deep within us. And true fulfillment in life comes when the mind opens to this inner ocean.

It’s not a matter of adopting some new idea, “not a question of knowing something,” as Lawrence says. It involves a unique experience — allowing the mind to become still, to transcend thought — and then the natural unboundedness of consciousness opens spontaneously to our awareness. This is Lawrence’s real thing.

A technique for transcending

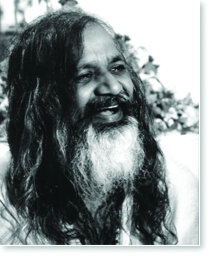

How are we to do it? From Maharishi we have the simple, natural, effortless technique of Transcendental Meditation, brought to light from the world’s most ancient continuous tradition of knowledge, the Vedic tradition of India. This technique allows the mind spontaneously to dive within, to settle down, to experience what Maharishi calls the simplest form of human awareness. This simple experience of inner wakefulness, of restful alertness, is a fourth major state of consciousness, which Maharishi terms Transcendental Consciousness.

More than 650 scientific research studies conducted all over the world during the past 42 years have documented the amazing array of benefits that flow from this simple, natural experience — from increased intelligence and creativity to improved health, from development of the personality to improved relationships, even improved quality of life for whole populations.

D.H. Lawrence seemed to have this experience spontaneously to some degree. And he intuited that this experience, the source of fulfillment and health and well-being, is what is largely missing from modern life. Everyone has the natural ability to transcend, to experience this fourth state of consciousness, Transcendental Consciousness. It need not be left to chance. Now, thanks to Maharishi, we have a simple, effortless technique by which everyone can have this experience and enjoy the profound renewal it brings.

REFERENCES

___________________________________________________

1. E.M. Forster, Letter to The Nation and Atheneum, March 29, 1930. Quoted in “D.H. Lawrence,” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D._H._Lawrence. Accessed June 4, 2012.

2. D.H. Lawrence, The Rainbow (first edition: London, Methuen & Co. [1915] (New York: Random House, Modern Library, 1943), 70-71.

3. D.H. Lawrence, ”The Real Thing,” in The Cambridge Edition of the Works of D.H. Lawrence, ed. James T. Boulton, Late Essays and Articles (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 309–310.