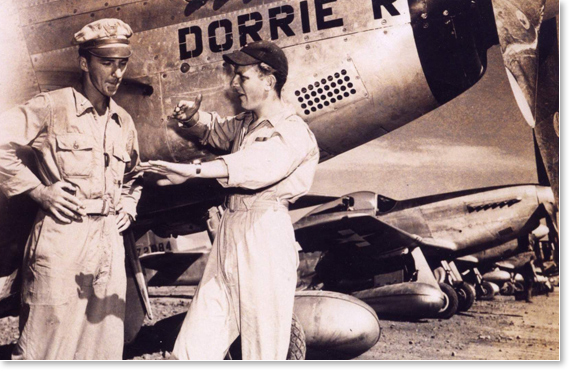

I was one of the 16 million people who served our country in World War Two. I was 18 when I enlisted, 19 when I graduated Luke Field in Phoenix, Arizona and three weeks into my 21st year when I landed on Iwo Jima, an 8 square mile island 650 miles from Japan. I quickly became familiar with death.

On March 7, 1945 our squadron landed on Iwo Jima on a dirt runway at the foot of Mount Suribachi. I looked out at the landscape as I taxied my Mustang to our parking area and saw huge piles of dead Japanese soldiers being pushed into mass graves, the sight and smell indelibly imprinted on my mind. It was a shocking sight for a young man just entering his 21st year to see. Our squadron area was next to a Marine mortuary where hundreds of dead Marines were being readied for burial, a sight that continued until the remains of nearly 7000 American Marines were buried in the cemetery. The fighting was fierce on this eight square mile Island 650 miles from Japan. Twenty one thousand Japanese soldiers lost their lives there and nearly 7000 Marines were killed.

I flew 19 very long range missions over Japan from Iwo Jima and flew with eleven young pilots, all of them friends, who did not return home. All in all I flew with 16 pilots who did not come back.

On one mission Al Sherren, my classmate from flying school called in “I’m hit and can’t see,” and he was gone. Robert “Pudgy” Carr also disappeared on that day. He was my tent mate.

Three of those killed were my wingmen. Danny Mathis in a mid-air collision with 26 other fighters when my wisdom teeth were pulled and I was grounded, Dick Schroeppel who was following me on a strafing run over Chichi Jima and Phil Schlamberg who disappeared from my wing in clouds on August 14, 1945 the day the war ended.

All of us knew who were fighting and why. Then it was over, one day a fighter pilot the next a civilian, no buddies, no airplane, nothing to hold on to, and no one to talk to. Life, as it was for me from 1945 to 1975 was empty. The highs I had experienced in combat became the lows of daily living. I had absolutely no connection to my parents, my sister, my relatives or my friends. I listened to some of the guys I knew talk about their experiences in combat and I knew they had never been in a battle let alone a war zone. No one that I knew who had seen their friends die could talk about it. The Army Air Corps had trained me and prepared me to fly combat missions but there was no training on how to fit into society when the war was over and I stopped flying.

I was not able to find any contentment, any reason to succeed, any connection to anyone that had meaning or value. I was depressed, unhappy and lonely even though I was surrounded by a loving wife and 4 sons. That feeling of disconnect, lack of emotions, restlessness, empty feeling of hopelessness lasted until 1975.

In 1975 I learned to meditate—I learned a technique called Transcendental Meditation. In just a few months life became meaningful to me and now, at 86.8 years of living, I can say that this meditation has brought me peace and contentment.

What makes the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan so difficult for our troops? War is always difficult for those on the front lines, but these wars are being fought in the countries of our enemies, on their territory, their homeland, their cities, and there are no established front lines or objectives to capture. Every citizen can be looked at as “the enemy,” every road as a dangerous road to travel, every pile of garbage might contain an IED ready to explode.

As I write this today, in October 2010, there have been 5745 of our servicemen and women killed and 86,175 evacuated from wounds or illness, 21.7% of the approximately 2 million who have seen active duty.

It has been estimated that 35-40% of those who have served since 2003 are victims of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Since the average age of the current military is 21, these veterans will require care for 50 or 60 years. The cost to care for our veterans as estimated by Stiglitz and Bilmes in their book The Three Trillion Dollar War will be $5,765.00 per veteran per year; a total that could reach 717 Billion Dollars just to service the estimated 2.1 million veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. This does not take into account additional costs to the Government for benefits to the families of the wounded and mentally ill veterans. Every veteran, either wounded or mentally ill affects everyone in his household adversely. The entire family suffers and has needs.

If I am an example of a recovered PTSD veteran, Transcendental Meditation should be offered to all veterans as an option. The cost per veteran for a lifetime of health is just 1/4th of the annual projected cost to the VA for one year of treatment. Why aren’t we pursuing this 5000 year old modality to help our young veterans and their families recover from the profound affect Iraq and Afghanistan has had on our military?

Article by Jerry Yellin, member of The Military Writers Society of America, CO-Chair Operation Warrior Wellness, a division of the David Lynch Foundation and the author of numerous books such as: Of War and Weddings,

The Blackened Canteen, The Letter and The Resilient Warrior.

To learn more about the effect of Transcendental Meditation on veterans with PTSD watch the video below.

Web references:

USA On Patrol – “Healing the Hidden Wounds of War” by Jerry Yellin

David Lynch Foundation Projects

Veterans Day: Can Meditation Help Veterans Overcome PTSD?